“We want to serve social progress, not social obscurantism and reaction. We want our work to be truly socially beneficial, to make modern scientific truth accessible to the broadest layers of the population. We demand freedom for our cultural work and the establishment of a cultural foundation. We are not from Mars; we are sons of this land, part of this people, with empty hands and pockets. We want to work in the interest of our country, the freedom, and progress of our suffering people”.

(From the Report at the Annual Assembly of KAB, September 8, 1935)

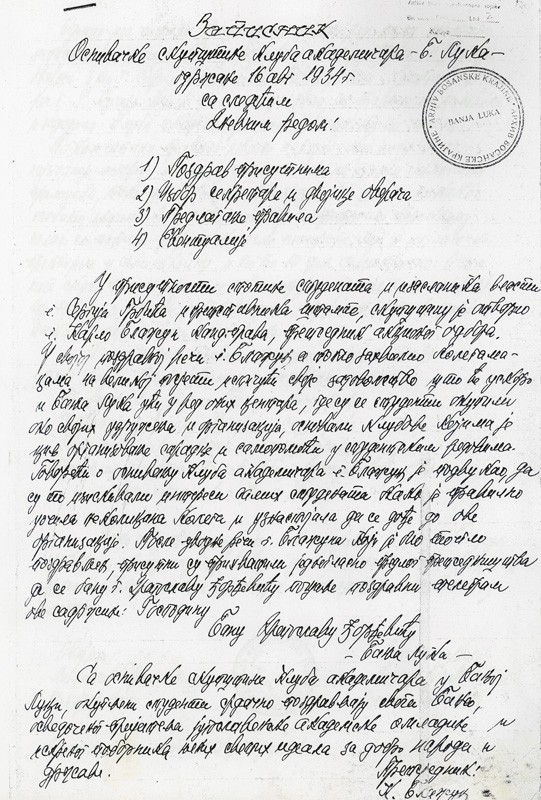

The organization “Academic Club of Banja Luka” (KAB) was founded a year earlier, on August 16, 1934.

According to Dubravka Škarec (Activities of the Academic Club of Banja Luka Before World War II), the initiative for its establishment came from a group of students from Banja Luka, among whom a particularly significant contribution to realizing this idea was made by Nikola Nikica Pavlić, a well-known communist and law student at the time. Throughout the existence and activity of this academic society in the pre-war years, he remained one of its most active members and leaders.

The establishment of KAB took place during a time when the student movement in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was gaining strength, initially aimed at improving the economic and political position of students. The regime’s terror against students fighting for better living conditions and the constant bloodshed at universities led to students expanding their struggle beyond the walls of university buildings into their towns and villages. In its early years, KAB had around 70 members. By 1940, just before KAB’s activities were banned, out of 250 students from Banja Luka, 150 were members of the organization.

Banja Luka students who were studying in Belgrade, Zagreb, and Ljubljana achieved, through the founding of KAB, the establishment of an organization in Banja Luka, alongside Sarajevo, Bihać, Bosanska Kostajnica, and Bijeljina. This organization continued to assist students during school breaks while also engaging in cultural, educational, and political activities.

In a 1937 leaflet issued by the KAB Board of Directors, it stated:

“The Academic Club in Banja Luka was established in difficult times, a time when the conditions for the education of most of our student youth were at their hardest, in a region that is culturally and significantly underdeveloped, with 72.8% illiteracy. At that time, among us Banja Luka students, the idea spontaneously emerged that we must take our destiny into our own hands, to create our own student organization through which we could both educate ourselves culturally and dedicate all our efforts and abilities to the cultural and educational upliftment of our community and region”.

While studying at universities in Zagreb, Ljubljana, and Belgrade, Banja Luka students were part of the progressive student movement, which was exceptionally active. Their efforts ranged from fighting for university autonomy to various actions directed against the dictatorial regime.

In order to understand the historical context of the growing student dissatisfaction, both with the socio-economic conditions and the political situation, it is essential to consider that KAB was established after the abolition of the “6 January Dictatorship” (January 6, 1929). With this dictatorship, King Aleksandar Karađorđević completely abolished parliamentary democracy, banned the activities of all political parties and trade unions, prohibited political gatherings, introduced censorship, and renamed the state to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

The Communist Party of Yugoslavia was the only organization that attempted to resist the dictatorship, calling the people to armed resistance, which was brutally suppressed by the police.

Prior to these events in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, the Obznana (Notification) (1920) and the Law for the Protection of the State (1921) had already banned the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, pro-communist trade unions, and curtailed several constitutional rights of citizens.

The dictatorship effectively ended after the Marseille assassination of King Aleksandar in 1934, which allowed the resumption of political party activities and led to new elections being held in 1935.

In the report on KAB’s activities presented at the annual assembly held in 1935, it was emphasized that the January 6th regime had equalized the living conditions of the student population with the extreme economic exhaustion of the working and peasant classes.

“An intellectual proletariat was created, which soon became aware of its situation and began an organized struggle for a better life in full solidarity with the most progressive social classes. The unprecedented and bloody terror of the Yugoslav fascist regime against the student masses and the constant bloodshed at universities alarmed the global public and instilled in the mass student body a firm conviction that only struggle and organizational unity could lead to improvements in the economic and political conditions of students”, writes Dubravka Škarec in her book about KAB.

KAB and the Communist Party of Yugoslavia

From its establishment until its ban in April 1940, the Academic Club of Banja Luka (KAB) served as a stronghold for the Banja Luka branch of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (KPJ) in all actions organized against the regime of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. KAB members Borivoje Ilić and Nikola Pavlić were also members of the SKOJ (League of Communist Youth of Yugoslavia) Local Committee during this time.

This political engagement and the close ties some members had with the KPJ led to their arrests, trials, and imprisonment.

Nikola Nikica Pavlić, a law student in Zagreb, was arrested in September 1936 and sentenced to prison, serving time in Sremska Mitrovica Prison. After his release, he completed his studies and continued his involvement in the revolutionary movement. He was also active as a writer and journalist, contributing to publications such as Pečat (Stamp), Naša stvarnost (Our reality), and Narodna Pravda (National Justice). At the onset of World War II, Pavlić edited Gerilac (Guerrilla), the first party newspaper in Bosanska Krajina, and later contributed to the Krajiške Partizanske Novine (Partisan Newspapers of Krajina). He passed away in April 1943 from typhus.

Activities of KAB from 1934 to 1940

During its existence in the period leading up to World War II, the members of the Academic Club of Banja Luka (KAB) were active in cultural and educational initiatives within Banja Luka itself. However, the “KAB members” were also engaged in activities in rural areas, working to raise cultural and educational standards in those communities.

Since the existing cultural and educational societies that KAB’s sections attempted to collaborate with were not interested, KAB organized a series of lectures on natural sciences, socio-political, and philosophical topics from 1934 to 1936.

From its founding, KAB members sought to provide broad support to underdeveloped villages in the Banja Luka region, searching for the most effective ways to educate rural populations about the concrete causes of their poverty.

Through this work, close ties were established between the Section of Agronomists, the cultural society Zmijanje, and rural communities in Glamočani, Čardačani, and Klašnice. Students gained firsthand experience of rural life and carried out practical initiatives aimed at improving living conditions in the villages.

The Beginnings of the Kočić’s Assembly

Members of KAB emerged as the main organizers of the commemoration of the 20th anniversary of the death of the writer and people’s tribune Petar Kočić on August 23, 1936. This event, in cooperation with the “Zmijanje” Cultural Association, was planned to consist of a series of appropriate performances in the village. However, just one day after the first gathering in Klašnice, the District Administration issued a ban on organizing this event.

In the explanation of this decision, among other things, it was stated that “outside the planned program, declamations were presented, or rather, verses were recited that have the least connection with the cultural work of Petar Kočić!?”

From issue 1073 of Vrbaske Novine (Vrbas Newspaper) from 1936, it is revealed that the district administrator was particularly bothered by the choral recitation of students titled “The Serfs”, which included the lines: “We have no light nor peaceful nights”.

Before its ban, KAB had organized around 150 various cultural-educational, political, and other activities.

KAB Members in the People’s Liberation War (NOB)

After the occupation of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and the proclamation of the Ustaša-led Independent State of Croatia in 1941, arrests of communists and all other opponents of the Ustaša regime began. Academic Club of Banja Luka (KAB) also fell under the pressure of Ustaša authorities.

Most members of the Academic Club of Banja Luka, like many other intellectuals of that time, joined the resistance against fascist forces. In the fight against fascism and domestic traitors during the People’s Liberation War, about 30 members or former members of KAB lost their lives. (Membership in KAB ended upon the completion of studies.) Some of the fallen revolutionaries include: Nikola Pavlić, Borivoje Ilić, Stjepan Pavlić, Milan Radman, Ranko Šipka, Rade Ličina, Danko Mitrov, Filip Macura, Josip Mažar Šoša, Duško Koščica, Zdravko Čelar, Radenko Stojnić, Vujo Oljača, Miloš Popović, Mirko Kovačević, Zdravko Lastrić, Branko Lastrić, Marijan Podgornik, Braco Potkonjak, Željko Barić, Miko Zec, Desa Radovanović, and Ljubica Mrkonjić. Eternal glory and gratitude to them and to all those whose names are not mentioned here.

KAB did not limit its activities solely to Banja Luka. According to historical documents, members of KAB were the initiators of the liberation of Teslić during the World War II.

KAB in Socialist Yugoslavia

After the end of World War II, KAB resumed its activities with a new generation of young intellectuals. Although there are no official records of when KAB restarted its work, photographs from 1946 show that activities were already being carried out at that time.

KAB’s activities focused on organizing numerous cultural and sports events, as well as participating in the reconstruction of Banja Luka after the catastrophic earthquake in 1969. Many of these events still exist today and are an integral part of the identity of the city on the Vrbas River.

In 1953, members of KAB held the first-ever event in Banja Luka called the Carnival on the Vrbas. This event, which played a significant role in enhancing the city’s tourism offerings and recognizability, featured activities such as diving from the City Bridge, dajak boat races (a unique type of boat used exclusively on the Vrbas River in Banja Luka), kayak and canoe races, and river-swimming competitions.

By the late 1970s, the event was renamed Encounters on the Vrbas, and since 1995, it has been known as Summer on the Vrbas.

A significant part of KAB’s rich history and contributions to the cultural development of Banja Luka is the Kočić’s Assembly (Kočićev zbor). This event, first held in 1965, aimed to preserve the traditions and memory of the great people’s tribune and writer Petar Kočić.

The initiator and visionary behind the Kočić’s Assembly was Fuad Balić, one of the most esteemed cultural and public figures in Banja Luka after World War II.

Sadly, Balić, along with Teofik Afgan and numerous other notable Banja Luka residents who were instrumental in revitalizing KAB and shaping its identity, is no longer with us. This absence of firsthand witnesses makes it difficult to fully capture the significance of KAB in the development of the city’s urban and cultural life. Moreover, through the Kočić’s Assembly, KAB succeeded in uniting urban and rural traditions into a unique cultural space.

One remarkable moment in the history of the Kočić’s Assembly was when Fuad Balić brought an entire symphony orchestra to Zmijanje for the event.

In recognition of its contributions, KAB was awarded the Order of Brotherhood and Unity in 1974, presented by Josip Broz Tito himself.

KAB also played a pivotal role in the academic development of Banja Luka. On its initiative, the University of Banja Luka was established, further cementing its legacy in the cultural and educational advancement of the city.

Who Abolished KAB?

The Academic Club of Banja Luka (KAB) was dissolved by a decision of the city authorities in the mid-1980s. The exact reasons for its closure remain unclear even today. One theory suggests that KAB resisted ‘integration’ into the Socialist Alliance of Working People (SSRN), as doing so would have meant losing its autonomy—a principle central to its founding in 1934.

Journalist Slobodan Pešević documented the following:

“When the author of these lines wrote a commentary with a similar headline for Večernje novosti (Evening News), he was summoned for an official meeting at the then Socialist Alliance of Working People (SSRN), Municipality of Banja Luka. In the former country, SSRN claimed authority over print and electronic media, including their content management.

It was a proper briefing and persuasion session, arguing that this was ideologically incorrect, that KAB had deviated from the party line, and that it had become a regressive organization. I did not agree with these assessments, but that’s where it ended”.

One assumption is that KAB members began to rebel against the actions of the authorities at the time, as various scandals related to the abuse of political power and functions started to emerge in public. The increasingly complex economic situation in the SFR Yugoslavia, worker dissatisfaction, numerous strikes, and political scandals began to surface in youth publications, which were becoming increasingly relevant in Slovenia, Serbia, Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

In addition to being focused on various cultural events, KAB enabled Banja Luka students to earn decent pocket money during the summer. Fuad Balić was also the initiator of this KAB activity, and a large number of Banja Luka students, born after World War II, worked occasional and seasonal jobs until the early 1990s.

Today, students in Banja Luka who wish to earn pocket money through occasional or seasonal jobs can still do so through the Youth Cooperative “KAB” p.o. Banja Luka. However, even though there are enough job opportunities, the number of students in Banja Luka and those willing to work is in decline.

KAB and Banja Luka Today

The remaining, living members of KAB still attempt to gather for so-called “round anniversaries”. However, they have not been spared the wartime traumas of being exiled from their own city, and ideological and national barriers have emerged among some of them.

This was most evident in correspondence conducted on the page of Café “Kajak” in 2009 and 2010. Memories of events in which they participated together and the times they shared often bring forth differing narratives and reveal the deep wounds left by the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

What they do share today, on the eve of the 90th anniversary of KAB’s founding, is a reluctance to speak publicly about the time they spent as KAB members. It is no surprise, then, that Miro Sojtarić’s 2009 initiative to attempt to revitalize KAB’s activities was met with more than lukewarm reception and numerous objections, citing how impossible such an endeavor would be in the current social and political context of Banja Luka.

Young people in Banja Luka know little to nothing about KAB. Most of them, unfortunately, we are convinced, have never stopped to read the text on the commemorative plaque dedicated to KAB, placed on the building of the National Theatre of the Republic of Srpska.

We ask: was the revolutionary spirit of Banja Luka extinguished with the dissolution of the old KAB, or should we wait for a new generation of brave young people to emerge? A generation that will want something more than politically organized concerts featuring obscure folk and rap stars who dominate the regional entertainment scene?

Has the educational system, Banja Luka’s academic community, a government that favors the obedient and compliant, religious institutions, and pro-government media created an environment where students now prefer party memberships and purchased diplomas over pursuing science and intellectual endeavors? Has the University, for the past three decades, been raising and “educating” mediocrities rather than intellectuals?

Do those who cannot come to terms with this pack their bags and leave this city, sending the message that leaving is an act of resistance?

Is that our bright future?

These are all questions that someone might answer in the future. Until then, KAB will remain in the memories of its still-living members and some of the older residents of Banja Luka, who gather every year in ever-diminishing numbers to commemorate August 16th.

The name KAB in Banja Luka remains on the city’s bridge, better known as the Venice Bridge, on a few commemorative plaques in Banja Luka, and in a café that bears this name.

The First Kočić’s Assembly

According to the Vrbaske Novine, the first Kočić’s Assembly was organized by KAB members, Marxists, in 1936, in collaboration with the Cultural Society of Zmijanje. The first part was held on August 23, 1936, in Klašnice, marking 20 years since the death of the renowned people’s tribune, Petar Kočić. However, the district authorities subsequently prohibited these gatherings from taking place in Kola and Klisina. You can read more about this event in issue 1072 of Vrbaske Novine from 1936, and here we provide the complete text published in that issue.

“The Main Committee of the Cultural Society of Zmijanje issued a proclamation regarding the commemoration of Petar Kočić on the twentieth anniversary of his death. With the cooperation of the academic youth (as stated in the proclamation) and all of Kočić’s comrades and friends, a celebration will be organized in the villages of Klisina and Kola near Banja Luka.

The academic youth that identifies as nationalists, members of the Association of National Academics of the Vrbas Banovina, are the only ones who can, with integrity and sincerity, raise Kočić’s banner and continue his national work. However, we have been informed that this group was not invited to participate in Kočić’s commemoration, and the references to academic youth in the proclamation do not apply to them.

According to information from the most reliable sources, the academics collaborating with Zmijanje in celebrating Kočić are Marxists from the Academic Club of Banja Luka. They will even publicly perform with their choral recitations…

The nationalist youth cannot forgive those public figures who, on the occasion of Kočić’s commemoration, recklessly claim that Bosanska Krajina in the people’s state is almost as backward and neglected as it was before. What weighs even more heavily on them is the collaboration of Kočić’s former comrades with young communists. What do Marxist choral recitations have to do with Kočić’s struggle for truth, justice, and freedom? What kind of freedom can the ideologues of the dictatorship of the proletariat bring to Bosanska Krajina? What kind of justice have the communists brought to the peasants? Who in Russia today dares to speak the truth?

The youth who claim that the great world war for the freedom of nations brought nothing; who declare strikes against their own state at universities; who argue that nationalism is a product of economic relations—such youth have nothing in common with Petar Kočić. For Kočić was a national bard. Kočić called for war with Austria. And, ultimately, he was not a nationalist for economic reasons.

The Marxist Drainac publicly attacked Miloš Crnjanski for being enamored with the ideas of the pre-war Bosnian nationalist youth from 1910.

And those ideas were Kočić’s ideas. Drainac was justified in his criticism because he spoke as a sincere Marxist. However, our young comrades in Banja Luka act much more cleverly: they skillfully camouflage themselves and undermine from within the national strongholds. Kočić’s commemoration is clear evidence of their cunning and audacity, as well as a manifestation of the political shortsightedness of our public figures. Was it not enough that Marxists infiltrated the women’s movement, the League for Peace, and other associations through KAB? Have not the previous conferences of Zmijanje with academics demonstrated the purposes for which even Kočić’s name is being used?

We will celebrate Kočić’s legacy not to obscure but to honor his work; he was ours from the beginning, and he will remain ours through memory and beyond. However, it is regrettable that alongside genuine admirers, there are those who seek to undermine Kočić’s legacy. It will be a tragic outcome for all of Bosanska Krajina if the Marxists manage to place the people’s tribune, Petar Kočić, among their leaders (like Hafabarec, Marinović, Cimer, Davičo, Pap, and their ilk)”.

Milovan Popović